How has the Bank Sector performed in the current market?

The bank sector has had a tough time over the last few years, with falling lending volumes, lending restrictions imposed, competitive margin pressures, heightened political risks, a bank tax levied, a Royal Commission called, public outrage over conduct, increasingly aggressive regulators, class actions, court cases, management changes, and increasing capital requirements (and that’s the short list!). Other than occasional short-lived relief rallies, the sector has largely underperformed the broader index since peaking in early 2015 up until the recent Federal election. On an absolute basis however, bank share prices have been quite resilient, dragged along by strong markets in general (in turn fuelled by lower interest rates).

More recently the banks have had some better news. The (relatively) more friendly Coalition retained government in a surprise election win in May, removing some of the more dire downside risks around negative gearing and franking credits. APRA then eased some of the macro-prudential restrictions around lending requirements, and the housing market has seen prices stabilise and even increase in some areas. Also, we have seen some funding cost pressures ease from earlier in the year. Immediately post-election we saw a strong bank sector bounce. Whilst they gave some of that relative performance back in the following months, they have largely held their own versus a surging market and have now matched the overall index performance since March this year. Does this consolidation phase indicate a turn in fortunes or just a breather before resuming the downtrend?

Are banks now cheap enough to buy?

The answer isn’t that simple unfortunately. Bank valuation measures have likely never been this divided.

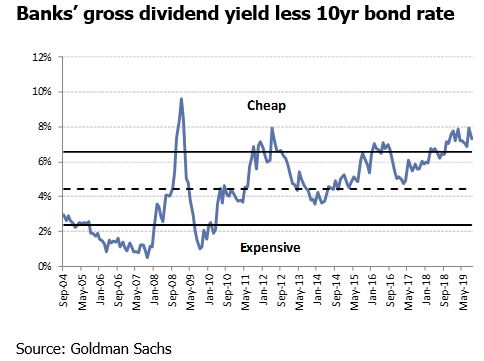

If we are purely valuing banks on a relative basis, i.e. relative to bond yields or cash, or relative to other sectors, then banks appear to be quite good value on historical averages, largely as a result of the extremes of what we are comparing to.

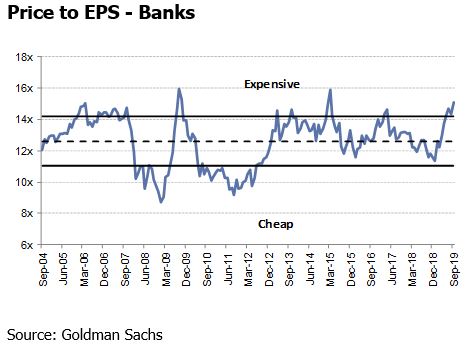

However, we are in extraordinary times for many asset values, and so on an absolute basis, i.e. price to earnings, or price to book value (compared to returns generated), they do not look to be good value at all compared to history.

Looking at relative valuations first. Often bank dividend yields get compared to bond yields as an alternative (although the answer is the same if compared to cash rates or even bank deposit rates). Given the collapse in bond yields, bank dividends, particularly when grossed up for franking, appear quite attractive. You can currently get around 1.0% 10 year government bond yield or an average 6% fully franked bank dividend yield, (>8.0% gross yield) – which looks attractive. The downside to this measure is that spot yield comparison doesn’t tell you anything about the risk to that yield for banks (elevated), the potential growth in those dividends (non-existent), capital requirements to fund those yields (increasing), nor anything around the multitude of regulatory risks the banks face.

On other measures, the picture is less rosy. While bank earnings (and dividends) have been under pressure given a slowing demand for borrowing, competitive pressures, huge increase in regulatory spend, fee pressures, and falling interest rates, bank multiples have actually held steady or risen. Price to earnings multiples on any other measure e.g. earnings per share or pre provision operating earnings to smooth out bad and doubtful debt cycles, are well above historical averages. It appears that whilst underperforming the index, bank valuations have nonetheless been dragged up materially by a surging market overall, given their size in the index.

So, to answer the question on whether banks are cheap enough to buy now, you need a strong view on where bond yields go from here and how the rest of the market performs, because it is hard to see too many positives from a bank specific earnings point of view to drive the sector. We are hardly about to enter an earnings upgrade cycle for banks for example. If we could get more comfortable on earnings, we would be more comfortable on valuations. Even holding earnings here versus a falling market may be enough. However, it is increasingly becoming a relative call rather than a fundamental one.

What are the key earnings drivers we need to watch from here?

The key issue for banks is that their earnings remain under pressure on both revenues and costs. Very low and falling interest rates are increasingly making life very tough for bank earnings with much of that yet to play out.

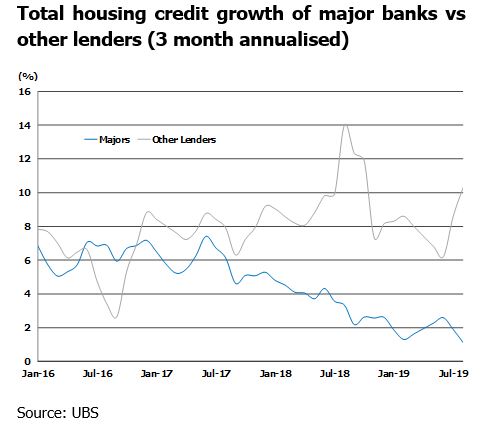

Whilst there has been some removal of lending restrictions on banks, and a recent increase in mortgage applications, overall lending growth for the majors remains weak owing to an uncertain economic environment, low housing sales volumes, absence of foreign investors, continued high consumer leverage and importantly, market share loss to the smaller players and non-banks. Banks are also still adjusting their approval processes to meet both regulatory and community standards around responsible lending and verifying customer expenses. This continues to weigh on supply, although perhaps less today than it did a few months ago. Also, low interest rates mean people pay down their loans faster, further pressuring net volumes. Should supply and demand improve further and prove sustainable (rather than just a short term bounce off low levels), that could be a positive change for the banks relative to recent history.

If low volumes weren’t tough enough, the banks are having to contend with heavy competitive pressures on their margins, especially in mortgages. In trying to compete for a slower growing pool of net new mortgages, the banks are pricing very keenly to attract the marginal dollar. Whereas in the past the majors could rely on their brand to protect their premium pricing, it appears those days are over, and the second-tier banks and non-bank lenders are competing very strongly and attracting flow. What’s more, with a large gap between front book pricing and back book pricing (i.e. new lenders get a better deal than those that already hold a mortgage), the target for the second-tier lenders is enticing and scary for the majors who have to match pricing or lose large volumes. It is hard to see this dynamic changing anytime soon. In fact, it’s likely to be exacerbated as interest rates fall. Non-banks and some second-tier banks (and eventually neo-banks as well) with a combination of lower capital and risk constraints, lower costs bases, or smaller back books are willing to take lower prices as they can still achieve good returns.

A low and falling interest rate environment will continue to make life very tough for bank earnings. With community and political pressure to pass on the interest rate cuts partially if not in full, the banks are running out of measures to offset. With large pools of deposits (that are used to fund mortgages) that already pay low to no interest, the banks are getting squeezed between lower mortgage rates they can charge and an inability to adjust their deposit rates down to offset. Banks also invest capital balances in interest rate products which will be getting a lower return. There continues to be more chance of rates falling rather than rising, keeping the pressure on. Either the banks lower mortgage rates as cash rates fall, to stay on-side of the government and community, and suffer a margin squeeze as a result, or they hold ground and risk customer backlash and market share loss from the smaller players and non-banks (something that is already happening). Not an enviable position. A change in rate expectations or some RBA assistance on funding costs (QE like) would be a something to watch to change the view.

An outcome of the Royal Commission and bank’s new found focus on meeting community standards has seen a continuation of rolling fee cuts coming through. This is further pressuring revenues. On top of this, banks continue to wind back, exit or sell a number of complementary businesses in insurance and wealth management. This again is seeing pressure on fee income. This will come to an end at some point, but the next year will be tough and it is making the banks even more susceptible to interest rate cuts.

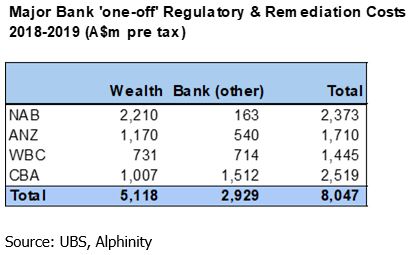

On the cost side, regulatory expenses continue to rise at a rapid rate. Via increased risk and compliance people and enhanced systems the regulators continue to demand more, especially in the wake of the Royal Commission and various bank run-ins with the regulator. On top of this, the various regulators feel compelled to justify their roles and budgets post a Royal Commission that left them in a poor light. As such they are being more aggressive and litigious, leading to more data requests and more court cases (and will continue to do so). Finally, we continue to see material costs related to remediation of past issues where the banks have done the wrong thing with their customers (largely in wealth, but banking as well). Not only is there the actual refunding of clients, but also the costs involved in working through all those issues internally. While neither we, nor it seems the banks, know where the end is, it would appear as if there is still more to come and potentially still material amounts of money to be remediated, and potential fines to be paid. If we look to countries like the UK as a precedent, it would suggest these costs can persist for a lot longer and be much higher than expected. If we thought regulatory costs were peaking or falling and that remediation costs were coming to an end, that would be a positive catalyst.

We would note that many banks are trying hard to respond with cost and efficiency programs to offset rising regulatory costs and falling revenue growth – however these programs themselves require upfront investments with benefits only further down the track. This is also complicated by regulators looking over their shoulder to ensure cost cutting doesn’t impact operational risk. Furthermore, banks are reluctant to be seen to be culling large numbers of employees or shutting branches when they are trying to regain community trust. We suspect however that the bank that wins on costs will win on earnings growth in the next few years.

Credit Quality is the final issue to consider. This relates to the amount of debts that go bad. Historically, and given the size of bank lending, this is the line that can cause the biggest volatility and really impact dividends. Given a combination of very low interest rates, high asset prices and low unemployment, the banks have enjoyed a bit of a golden era in terms of very low and falling loan losses. This has helped earnings for a number of years as provisions fell and write-backs continued. It does appear as if this help has now stopped, but it is yet to become a material headwind. All the banks are currently reporting significantly lower losses than normal. At some point those losses will deteriorate. Even if only marginally, given very low earnings growth, some deterioration will be a decent headwind to growth (and possibly dividends in the extreme). This does not appear to be a near term issue, but when valuing banks, it is worth remembering that bank sustainable earnings are actually overstated at the moment due to low losses.

So where does that leave bank positioning?

We remain positioned underweight the sector for now.

Attractive relative valuations restrain us from becoming too negative on the sector, as you likely get occasional bouts of bank relative performance on ‘valuation’ or defensive grounds (depending on the tweet of the day, no doubt!). Equally it is hard getting excited about these relative valuations, when absolute valuations are so stretched, and we see continued earnings pressure near term. It is likely that over time the weak earnings outcomes will continue to drive underperformance, as will continued negative regulatory headlines. Whilst bank return on equity has consistently fallen for many years now to their lowest levels since the early 1990’s, it is still very difficult to definitively say where they will bottom out, or where regulators, the government or the community will let them settle. It is hard to imagine consistent outperformance in that environment.

We would become even more negative if we saw a pick up in bad and doubtful debts, although these cycles play out over long time frames and whilst we expect minor pick up from historically low levels, we don’t see anything material on the near-term horizon. We would become more interested in the sector if we saw their relative earnings outcomes stacking up well versus other sectors, and the downgrades stopped and turned to upgrades.

It is worth pointing out here as well that historically there has been (on average) an inverse correlation in performance of the two large sectors in the market, banks and resources, i.e. one tends to outperform when the other underperforms. This is partially macro related (different conditions suit their earnings differently), but also cash flow related whereby investors tend to fund one with the other depending on their relative attractiveness. For much of the last three years, industry conditions for resources – especially the iron ore companies – have been favourable, making the difference to the banks even more stark. However, since the trade war rhetoric picked up earlier in 2019 and global growth slowed further, the outlook for the sector has become more uncertain. This is another factor we need to consider when looking at the banks from a portfolio construction perspective.

On a bank-specific basis, in general we continue to see better relative value and earnings prospects in the business banks (e.g. NAB) as opposed to the retail or mortgage banks (e.g. CBA), although it must be said they all have issues that concern us. The business banks have relatively less exposure to the geared consumer and housing, and as such less exposure to the tougher parts of the market currently. We also favour banks that are firmly focussed on their cost base and responding to the current environment. We believe flat-to-negative cost outcomes are likely required to combat a tough top line and to grow earnings. This again steers us more towards the business banks currently.

We acknowledge that a lot of bad news has played out for the banks already, meaning we are very alert to stabilisation in news flow or earnings impacts, or even slightly more positive tones that would be positive for bank performance. However, it is still hard to see a more positive environment in the near term with interest rates falling, a focus on capital levels, ongoing regulatory scrutiny and in some cases, dividends remaining under the spotlight. We know a negative credit cycle will come eventually and that would make things even worse when banks are already stretched. We would prefer to buy when absolute valuations look more attractive, rather than just relying on relative ones, but at the very least we need the news flow and negative environment to change.

Author: Andrew Martin, Portfolio Manager

The information in this publication is current as at the date of publication and is provided by Alphinity Investment Management ABN 12 140 833 709 AFSL 356 895.

It is intended to be general information only and not financial product advice and has been prepared without taking into account your objectives, financial situation or needs. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance.