Last year, Alphinity’s Head of ESG and Sustainability, Jess Cairns, visited Western Australia to meet with several mining and energy companies and five Traditional Owner groups in the Karratha and wider Pilbara region. As part of the research trip, she joined the Robe River Kuruma Aboriginal Corporation for a two-day cultural immersion. The elders shared personal views on the impact of mining, both good and bad, and raised concerns about the health of a critical waterbody called the Bungaroo aquifer.

The research trip gave us unique access to an important stakeholder group in the Pilbara and offered direct perspectives into First Nations’ priorities, their influence and the ongoing permitting risk for miners. We also gained knowledge into Native Title and Land Council Corporations and the different obligations mining companies have when it comes to cultural heritage.

Building on these insights, Senior ESG and Sustainability Analyst, Moana Nottage, undertook a similar research trip to engage with mining companies and Aboriginal Corporations, including site visits to South32’s Boddington bauxite mine and Pilbara Mineral’s Pilgangoora lithium mine. Our research aimed to assess the mining sector’s progress in addressing important ESG risks including nature, First Nations considerations, decarbonisation, artificial intelligence (AI) and workforce risks with a particular focus on psychosocial safety.

Insights

Rehabilitation and nature

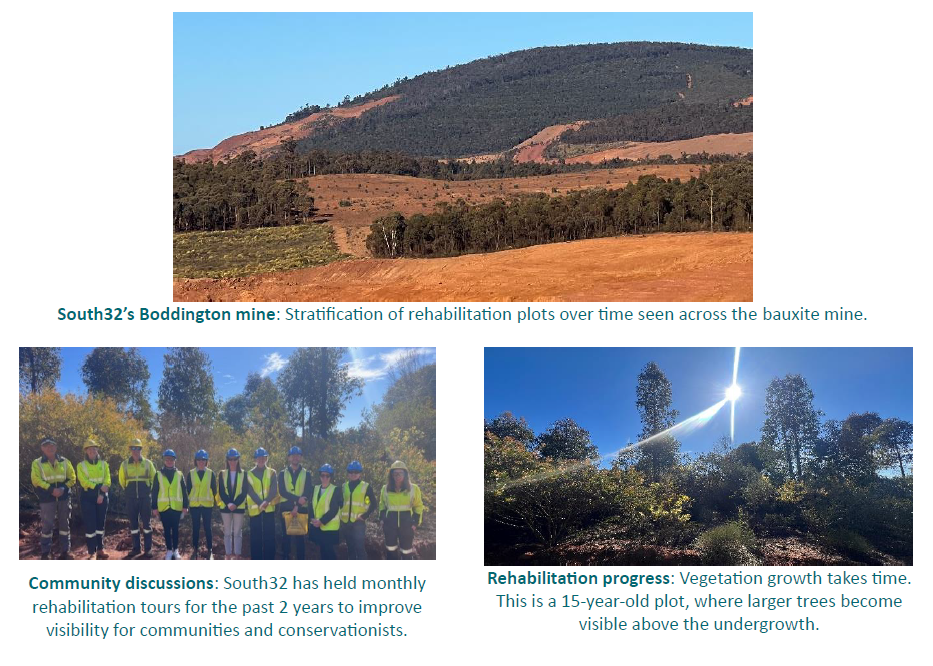

The mining sector has been managing land impacts for decades, but community expectations and regulatory standards continue to escalate across Western Australia. South32’s Boddington bauxite mine, situated two hours from Perth, has faced pushback from local communities and environmental groups. The operation spans a 24-kilometre lease and intersects with old pastural land and native forest, creating complex sensitivities around dust, noise, water management and biodiversity preservation.

The threatened Jarrah Forest ecosystem, home to the iconic black cockatoo, has emerged as a focal point of contention. These birds depend on tree hollows for nesting, which can take up to 200 years to develop naturally. While the state government banned native forest logging in 2024, mining-related clearing remains permissible under appropriate environmental permits. However, this increases pressure on mining approvals and expansion plans, which can disrupt the performance of mining companies. Given Boddington’s strategic importance as a nearly 5 million-tonne annual bauxite producer, these environmental challenges require proactive management and oversight.

South32 has responded by significantly enhancing its stakeholder engagement and rehabilitation efforts. The company conducts monthly tours to help residents and environmental advocates better understand the mine’s biodiversity profile and vegetation efforts. Moana joined this tour and was encouraged by the outcomes of the nature program with mature regrowth areas (20+ years post mining) achieving 75-90% of native flora species return. This is supported by an impressive seed bank of over 200 species, extensive biodiversity monitoring and eDNA technologies. The long tenure of the rehabilitation team, some with over four decades of experience at Boddington, adds depth and continuity to the program.

That said, it felt like the regulatory landscape in Western Australia continues to tighten. Environmental permitting has become more stringent, requiring miners to invest in biodiversity experts, collect species data, plan land offsets early and demonstrate deep ecological understanding to secure approvals. South32 has scaled up rehabilitation, increasing from historical levels of 100 hectares annually to 300 hectares last year. However, this will need to rise further to 400–500 hectares per annum to meet regulatory requirement to reduce disturbed land from 42% to 25% within three years. The risk of environmental permitting delays was also highlighted by Capricorn Metals, which experienced a 2-year approval delay at a gold mine due to biodiversity concerns.

First Nations

A highlight of the trip was meeting with the Robe River Kuruma and Yinhawangka Aboriginal Corporations. Their insights on co‑management, compensation and shared benefits that underpin agreement modernisation highlighted the evolving relationship between mining companies and First Nations people. It was encouraging to hear more miners engaging in informal, proactive outreach, an approach that Traditional Owners clearly value. One pioneering example of improving Indigenous participation and equity, was highlighted by Fortescue. It has launched a lending program specifically designed to support First Nations businesses and address systemic barriers in accessing capital.

Nevertheless, our conversations also highlighted the sophisticated objectives of these Aboriginal Corporations to address historic power imbalances with mining companies. They are actively seeking redress for past compensation shortfalls, increased royalties and better shared benefits arrangements across employment and procurement. Smaller mining companies also highlighted that meeting traditional owners can be challenging, due to the rising number of requests across the mining sector for deep involvement in cultural heritage assessments and benefit-sharing negotiations. It’s clear that dialogue on these priorities will continue between Traditional Owners and miners in the Pilbara, with support from federal and state governments.

Technology and AI

Technology continues to reshape modern mining, but AI adoption remains inconsistent across companies. Some use-cases gaining traction include autonomous vehicles, AI-assisted digging and mineral recovery optimisation from the likes of Fortescue, Capricorn Metals and Sandfire. It was a pleasant surprise to witness Tomra Systems’ advanced sorting technology, typically used in return‑and‑earn bottle machines and only commenced operations 6 months ago, being deployed at industrial scale to sort ore grades at Pilbara Lithium’s (PLS) Pilgangoora lithium mine.

New

Decarbonisation

Decarbonisation is a major priority across the mining sector, driving substantial investment in electrification infrastructure and fuel transition to lower-emission energy sources such as gas. For remote sites, scaling reliable green electricity supply and transmission remains a challenge, along with securing low-emissions vehicles.

Mining companies are adopting mixed-energy approaches, typically combining gas, batteries, solar, and wind. At Pilgangoora lithium mine, PLS’ shift from diesel to gas has cut energy costs by 20%, delivering financial benefits. The company is also working with Calix on a demonstration plant featuring the world’s first electric calciner (industrial furnace) which is backed by a $35 million government grant. This innovation could reshape Australia’s lithium industry by enabling the export of higher‑grade lithium concentrate, reducing both transport costs and emissions.

Workforce

Given the cultural challenges confronting the mining sector in recent years, workforce culture featured prominently during our company meetings. Encouragingly, the sector continues to take a holistic approach to workforce and psychosocial safety, integrating mental health support and fostering positive workplace culture. More progressive companies, like PLS, are shifting from the traditional 2:1 FIFO roster (two weeks on site, one week off) to a more balanced an 8:6 structure (eight days working, six days off). Despite higher operational costs, this scheduling change delivers substantial mental, physical, and relationship benefits for workers.

Liontown Resources is leading an interesting study that extends beyond assessing psychosocial hazards to explore the role of targeted mental health programs and positive humour in FIFO environments. Meanwhile, Newmont has introduced upgraded accommodation standards, featuring improved lighting, dedicated women’s facilities, and security cameras, investments that other mining companies such as BHP and Rio Tinto continue to expand across their operations.

Conclusion

This trip highlighted the steps that mining companies are taking to strengthen relationships with First Nations communities, advance land rehabilitation and prioritise workforce wellbeing and safety. The collective energy suggested an industry actively shaping a more responsible future in mining. Investment in new technologies and decarbonisation initiatives were equally apparent across operations. Nonetheless, the sector is clearly navigating interconnected challenges, particularly those relating to nature, community and cultural heritage.

On-the-ground perspectives sharpen our ESG risk assessments and deepen our understanding of sector priorities. They not only enable us to better evaluate risks and opportunities as investors, but also enhance the quality of our engagement with portfolio companies. Overall, these insights confirmed that environmental regulations, permitting risk and First Nations considerations remain key investment considerations for mining companies operating in Western Australia, as well as miner operating globally.