Applying the Sustainable Development Goals to investing in Australian shares

Responsible Investing has been around for a long time, but the COVID pandemic seems to have transformed it into a secular trend that could become the dominant strategy of the 2020s. Investors are now spoilt for choice with an ever-expanding menu of responsible options, such as ESG Funds, Ethical Funds, Sustainable Funds, Green Funds, Impact Funds and so on, although some are long on promises and short on track record. While they are often seen as pretty much the same thing, the funds themselves may end up investing in very different companies and investors need to do some research to make sure they are comfortable with the products and operations of the companies that end up in their portfolios. A Charter or some other summary of the fund’s objectives often helps in clarifying this for prospective investors.

So how can investors assess the true underlying sustainability of an investment and get comfortable that they will not have to forego returns in order to feel better about what they are investing in? The answer lies in combining a rigorous and consistent sustainable lens with an equally rigorous and proven investment process. There is a wide array of approaches to apply a trusted sustainable lens to a portfolio. One such example, is the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which is an internationally agreed framework of goals with the aim of achieving a better world. Below we explore how the SDGs can be used to find Australian companies ‘doing good’, i.e. those making net contributions towards achieving one or more of the SDGs and how to avoid companies whose activities are inhibiting the achievement of the Goals.

The origins and evolution of Sustainable Investing

The origins of Socially Responsible Investing (SRI) can be traced back to the Quaker and Methodist movements in the eighteenth century. Around that time, Methodist leader John Wesley urged his followers to shun profiting at the expense of their neighbours. It was in the 1960s and 70s that SRI started to become more prominent along with the US civil rights movement, an increasing awareness of environmental issues and the start of the anti-apartheid movement in which a number of universities, churches and cities pulled their investments in companies with operations in South Africa.

SRI has seen many iterations and interpretations since then, moving from merely excluding certain activities to also negatively screening out stocks based on the Environmental, Social and/or Governance (ESG) qualities of a company. ESG tends to focus on the internal operations and processes of a company and rather than on external activities that might cause good and/or bad outcomes. These days ESG is firmly part of mainstream equity investing, and there are few managers who would not at least say they include some degree of ESG consideration in their investment efforts. We consider companies with good ESG practices to be ‘doing it well’.

More recently there has been growing interest in Impact Investing, which deploys capital to achieve certain social or environmental outcomes. One major issue has been the lack of an agreed and unified system defining what a ‘good’ or ‘bad’ outcome might be, and the activities that cause them. There is also some debate around whether buying shares in companies on the secondary market can really be having an impact, or whether you are just joining efforts that are already being made. This view would suggest that Impact Investing is most credibly exercised by asset-owners in the unlisted space. Notwithstanding this, we feel that aligning yourself with companies doing good for society is still a worthy ambition and, if nothing else, improves those companies’ financial ability to pursue activities contributing to the goals. In addition, if executed well, it can also be financially rewarding.

The Sustainable Development Goals

In 2015, the United Nations agreed to a unifying set of 17 goals which, if achieved by 2030, would make the world a significantly better and more equitable place to live. The goals address high priority problems which must be solved in order to reach desirable levels of global development in a sustainable way. They address many of the global challenges we face, including poverty, inequality, climate change, environmental degradation, peace and justice. The 17 goals shown below have been expanded into 169 detailed underlying targets.

This next wave, Sustainable Investing, aims to actively support positive investment outcomes, not just try to avoid negative outcomes. One challenge is that the SDGs were primarily designed to direct government priorities rather than business activities: they largely describe what countries need to do (or stop doing) to achieve the goals, and they identify the structural changes that need to take place in the economy. While there are some goals that companies might struggle to address, the goals can still be useful in mapping prospects for Australian companies.

An issue for developed countries like Australia is that for some SDGs, the gap between the desired outcome and the current situation can be quite small or even non-existent: it is developing countries that need more action to close some of the much larger gaps. For example, the goal of defeating poverty – which is defined by the UN as an income under $US1.90 per person per day – is not relevant for Australia. While there is certainly relative poverty in Australia, which should be addressed by government and might be able to be addressed by some company activities, absolute poverty as defined by the UN is virtually non-existent. But there are plenty of companies which can contribute significantly to other SDGs by doing things such as producing lithium for batteries or steel for infrastructure, developing hydrogen technologies to reduce carbon footprint, or providing healthy food for people in Australia and beyond.

For more domestically-focused companies, it’s helpful to remember that some activities also help to maintain certain goals. For example, healthcare companies can continue to provide products and/or services which maintain the goal of Good Health and Well-being (SDG 3).

SDGs relevant to Australian companies

Of the 17 SDGs, we have found that Australian companies can provide the most material contribution towards the following:

- Zero Hunger/Good nutrition (SDG 2)

- Good Health and Well-being (SDG 3)

- Quality Education (SDG 4)

- Affordable and Clean Energy (SDG 7)

- Infrastructure (SDG 9)

- Sustainable Cities (SDG 11)

- Responsible Consumption and Production (SDG 12)

- Climate Action (SDG 13)

A number of Australian companies are able to address two of the SDGs – Responsible Consumption and Production (SDG 12) and Climate Action (SDG 13). Sectors that score well within these Goals are resource companies producing essential metals for infrastructure and economic development, healthcare, insurance and utilities, waste management, technology and telecommunications.

It is important to remember that any economic activity almost inevitably has a degree of negative impact, so any assessment of a company’s SDG performance needs to take the negatives into account, not just the positives. Sectors such as energy and consumer staples all have significant resource footprints in water, waste and emissions and tend to score poorly on the waste (SDG 12) and climate (SDG 13) goals. Some consumer staples companies can also contribute to obesity and lifestyle disease by producing highly-processed food or sugary drinks; these tend to score poorly on nutrition (SDG 2). Assessing and awareness of the negatives also provides scope for engagement with the company, to understand and encourage greater efforts towards sustainable outcomes.

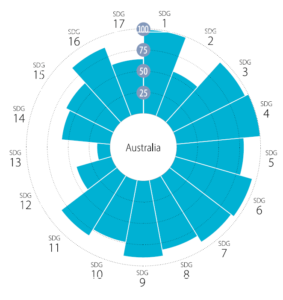

Australia is currently ranked 37th out of the 166 nations assessed by the UN: while a long way from the bottom it is also a long way from the position in country rankings we are accustomed to seeing, which tends to be well inside the top 20 or even top 10. This suggests there is much room for improvement, and to the extent that the lagging issues are addressable by companies, your wealth could have a role to play in achieving this.

Australia still has a long way to go

Source: https://dashboards.sdgindex.org/profiles/AUS

Applying the SDGs to Australian companies to build a portfolio

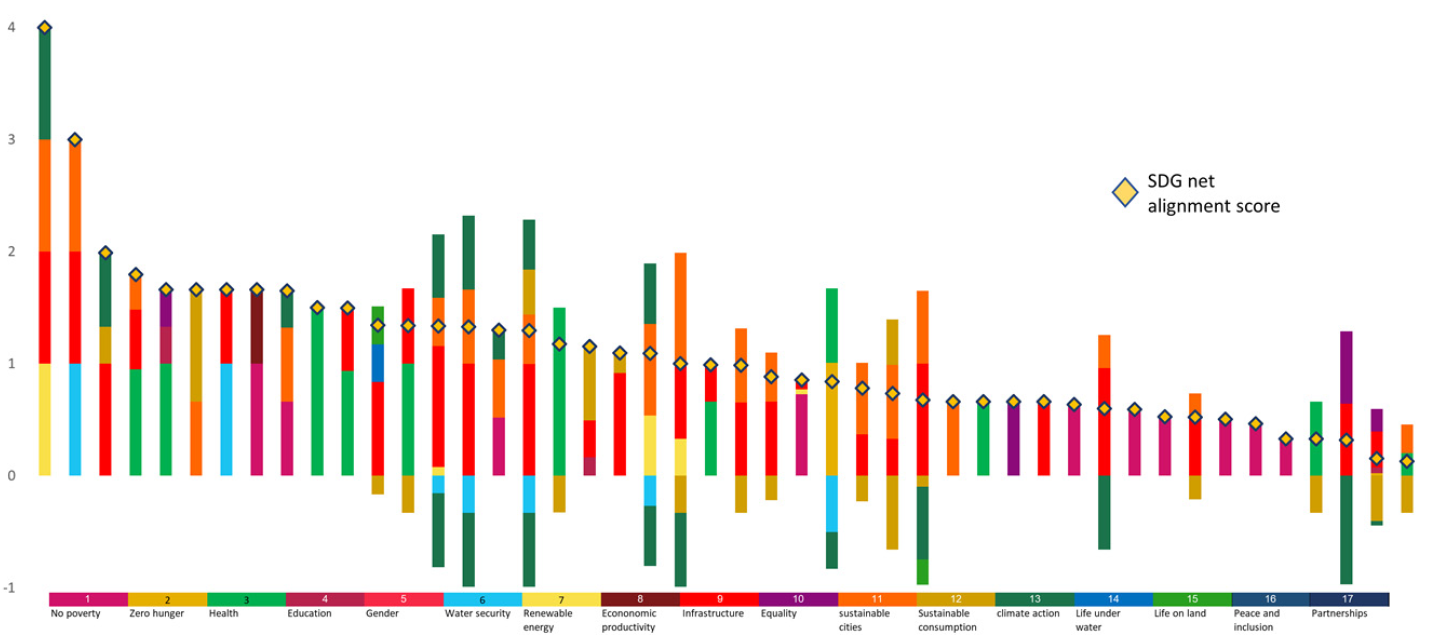

SDG considerations can be applied to the Australian equity market by seeking to identify the opportunities and risks facing each company in the investable universe. This can become a positive screen for funds to supplement the more conventional and much easier negative screens, i.e. excluding companies engaged in undesirable activities and companies with poor ESG practices. We have evolved this to arrive at a Net Alignment Score for each company based on its products/services and operations. This is a high-level process which requires good data and, importantly, sound judgement. Leaders in Sustainable research, such as Citi and MSCI, our external experts and other sustainable thought leaders help us to apply the SDGs to our investment process. Individual company analysis has the additional benefit of helping us to identify companies that might benefit from macro tailwinds and areas of company engagement. The chart below is an example of the number of Goals partially or fully addressed by a portfolio of about 40 stocks and the net contribution of each company. It is not a tool for stock selection though, merely a demonstration of each company’s contribution towards sustainability.

Source: Alphinity

Examples of companies that contribute positively to SDGs

Fortescue Metals Group – The future of sustainable cities

As an iron ore producer Fortescue Metal Group aligns most positively with SDG9 (infrastructure and innovation) and SDG11 (sustainable cities).

As an iron ore producer Fortescue Metal Group aligns most positively with SDG9 (infrastructure and innovation) and SDG11 (sustainable cities).

Although it also has some negative alignment with SDG13 and SDG6 due to emissions and resource use, its operational measures and commitments demonstrate the intent to transition to a low carbon future and manage adverse operational impacts.

For example:

- Iron ore operations to be Carbon neutral by 2030 (Scope 1 and 2)

- Investment in green technologies and opportunities through their wholly owned subsidiary Fortescue Future Industries (FFI). 10% of Fortescue profit is to be allocated to FFI

- FFI research and trials into green shipping for ammonia transport, hydrogen power, hydrogen heavy duty fleet, green steel etc

Risks and engagement: Fortescue has had some issues in dealing with traditional owners which are being monitored. Areas of engagement include Heritage management, FFI investment priorities, governance and structure, low carbon initiatives, Pilbara energy connect, hydrogen trial and Ironbridge issues and workforce management.

Sonic Healthcare – Supporting health and wellbeing with a leading patient and clinician focus

Sonic has grown to become one of the world’s leading healthcare providers with operations in Australia, the USA, Germany, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, Belgium, Ireland and New Zealand.

Sonic has grown to become one of the world’s leading healthcare providers with operations in Australia, the USA, Germany, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, Belgium, Ireland and New Zealand.

The Group provides highly specialised pathology/clinical laboratory and diagnostic imaging services to clinicians (GPs and specialists), hospitals, community health services, and their patients.

Sonic strongly aligns with:

- SDG3 which aims to ensure healthy lives and promote wellbeing for all at all ages

- SDG9 through development and management of high-quality technically advanced laboratories, infrastructure, and ongoing investment in research and development

Risks and engagement: The main negative associated with this type of healthcare is waste. Sonic has appropriate policies in place and manages all waste in accordance with regulations.

Incorporating SDGs into an investment process

The first step in sustainable investing is to define the investable universe by identifying companies that have strong ESG characteristics and are able to contribute towards achieving one or more of the UN SDGs. The activities of these companies also need to be compatible with the Fund’s charter.

The second and equally important step is to find fundamentally attractive investments among these sustainable companies, as determined by experienced investment professionals using a rigorous and tested investment process.

The end result is a portfolio of sustainable companies ‘doing good’ and ‘doing it well’ by supporting sustainable development while also providing compelling investment returns over the medium term.